End-to-End Guide: Preparing Raw Text Data for NLP Models (Cleaning, Normalization, and Tokenization)

Natural Language Processing (NLP) models are only as good as the text you feed them. Even the most advanced transformer will underperform if your dataset is full of noise: inconsistent casing, weird Unicode characters, HTML tags, broken tokens, or duplicate lines.

This guide walks through an end-to-end workflow for preparing raw text data for NLP tasks:

- Cleaning messy raw text

- Normalizing text consistently

- Tokenization strategies (word, subword, character)

- Practical tips and Python examples

- Tradeoffs between approaches, with tables and diagrams

Whether you’re building a sentiment classifier, a chatbot, or a semantic search system, these steps will dramatically improve model performance and reliability.

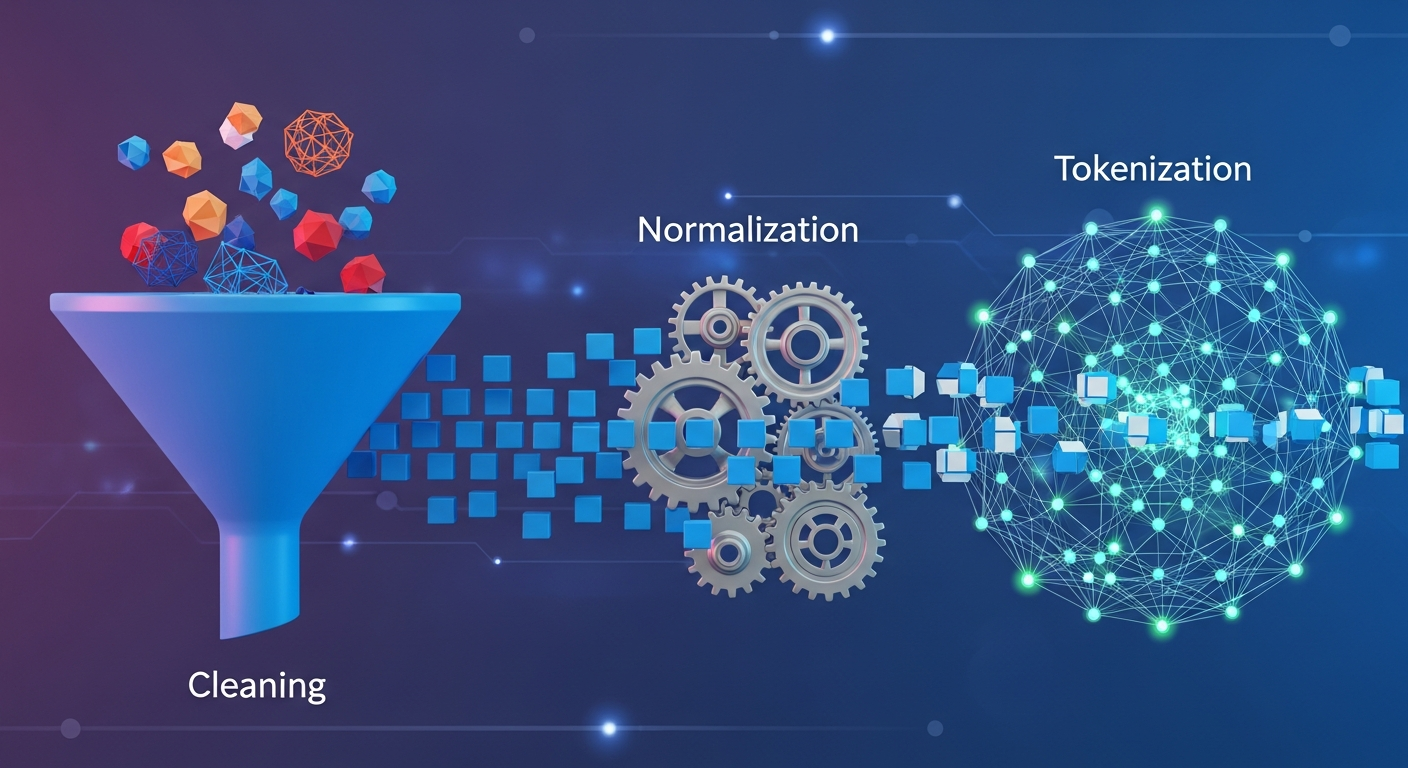

1. Overview: The Text Preparation Pipeline

Before diving into code, it helps to see the whole process.

At a high level, almost every NLP project follows some variation of:

graph TD

A[Raw Text Sources<br/>logs, HTML, PDFs, social media] --> B[Ingestion & Deduplication]

B --> C[Cleaning<br/>remove HTML, noise, junk]

C --> D[Normalization<br/>case, unicode, punctuation]

D --> E[Tokenization<br/>word / subword / char]

E --> F[Feature Representation<br/>IDs, embeddings, counts]

F --> G[Model Training / Inference]

In this post, we’ll focus on C–E: cleaning, normalization, and tokenization.

2. Collecting and Inspecting Raw Text

Before you clean anything, look at your data. A quick initial inspection saves you from guesswork.

2.1 Quick Inspection in Python

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv("raw_text.csv")

print(df["text"].head(5).tolist())

Things to look for:

- Encoding issues (

\ufeff, é)

- HTML tags or markdown fragments

- Logs, timestamps, or stack traces mixed with text

- Non-language content (URLs, code, emojis)

- Duplicate or near-duplicate lines

If you have large text samples in text files (e.g., scraped corpora) and need to sort or deduplicate lines before loading into Python, an online utility like the htcUtils Text Sorter & Cleaner can be handy for quick preprocessing or sanity checks.

3. Cleaning Text: Remove Noise First

Cleaning removes content you definitely don’t want the model to learn from. This is task-dependent: what’s noise for a sentiment classifier might be signal for a spam detector.

3.1 Common Cleaning Steps

| Cleaning Step |

When to Use |

Notes |

| Strip HTML/Markdown |

Scraped web pages, blogs |

Use an HTML parser instead of regex if possible |

| Remove boilerplate |

Pages with headers, footers, nav menus |

Avoid teaching the model repeated templates |

| Remove URLs/emails |

Most semantic tasks, unless URLs are important |

Can replace with placeholder tokens |

| Remove code/logs |

When modeling plain-language text only |

Use regex or heuristics |

| Deduplicate lines/docs |

Large scraped corpora, noisy logs |

Reduces bias from repeated content |

| Drop very short/long text |

Based on task (e.g., tweets vs. full articles) |

Filter out outliers |

3.2 Removing HTML Safely

Avoid using regex to strip HTML. Parsers do a better job:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

def strip_html(text: str) -> str:

soup = BeautifulSoup(text, "lxml")

return soup.get_text(separator=" ", strip=True)

html = "<p>Hello <b>world</b>! © 2024</p>"

print(strip_html(html))

# Hello world! © 2024

3.3 Removing URLs, Emails, and Mentions

import re

URL_RE = re.compile(r"https?://\S+|www\.\S+")

EMAIL_RE = re.compile(r"\b[\w\.-]+@[\w\.-]+\.\w+\b")

MENTION_RE = re.compile(r"@\w+")

def remove_noise(text: str) -> str:

text = URL_RE.sub(" <URL> ", text)

text = EMAIL_RE.sub(" <EMAIL> ", text)

text = MENTION_RE.sub(" <USER> ", text)

return text

sample = "Email me at [email protected] or visit https://example.com @john"

print(remove_noise(sample))

# Email me at <EMAIL> or visit <URL> <USER>

Using placeholders like <URL> instead of deleting entirely can preserve structure (e.g., “Click the link”) without leaking sensitive data.

3.4 Deduplication

Duplicates in your training data can lead to overfitting and bias.

df = df.drop_duplicates(subset=["text"]).reset_index(drop=True)

For raw .txt or .csv lists, especially large ones, quick manual deduplication and sorting can be done in a browser using tools like the htcUtils Text Sorter & Cleaner, which can remove duplicate lines and sort content before you pull it into a pipeline.

4. Normalization: Make Text Consistent

Once you’ve removed obvious noise, the next step is making the remaining text consistent. Normalization ensures similar inputs map to similar forms.

4.1 Lowercasing (and When Not to)

Default for many NLP tasks is to lowercase everything:

def normalize_case(text: str) -> str:

return text.lower()

But lowercasing isn’t always ideal:

- Named entities: “US” vs “us”

- Product codes: “Model X”, “iPhone 11 Pro”

- Case-sensitive tasks: NER, some question answering tasks

A common compromise:

- Train an uncased model for coarse tasks like sentiment classification.

- Train a cased model for fine-grained tasks like NER or QA.

When preparing text snippets manually (documentation, training samples, pattern lists), a utility like the htcUtils Case Converter is convenient for quickly toggling between lowercase, UPPERCASE, Title Case, or snake_case, especially when you’re defining rule-based dictionaries or canonical labels.

4.2 Unicode Normalization

Different Unicode code points can represent visually identical strings. Use unicodedata:

import unicodedata

def normalize_unicode(text: str) -> str:

# NFC is often fine for most tasks; NFKC slightly more aggressive

return unicodedata.normalize("NFKC", text)

text = "cafe\u0301" # 'e' + combining acute

print(text, len(text))

normalized = normalize_unicode(text)

print(normalized, len(normalized))

This avoids subtle issues like "é" being treated differently depending on how it’s encoded.

4.3 Whitespace Normalization

Uneven whitespace is common in scraped content or logs.

import re

WS_RE = re.compile(r"\s+")

def normalize_whitespace(text: str) -> str:

text = text.strip()

text = WS_RE.sub(" ", text)

return text

s = "Hello \t world\n\n !"

print(normalize_whitespace(s))

# Hello world !

4.4 Punctuation and Special Characters

You don’t always want to strip punctuation completely. It often carries meaning:

- “What?!” vs “What”

- Sentiment: “good!!!”

- Contractions: “don’t”, “can’t”

You can:

- Keep punctuation but separate it as separate tokens.

- Normalize repeated punctuation (e.g.,

"!!!" → "!").

import re

REPEAT_PUNCT_RE = re.compile(r"([!?.,])\1{1,}")

def normalize_punctuation(text: str) -> str:

# Collapse repeated punctuation

text = REPEAT_PUNCT_RE.sub(r"\1", text)

return text

print(normalize_punctuation("What?!?! That's crazy!!!"))

# What?! That's crazy!

5. Language-Specific Considerations

Normalization is not one-size-fits-all. Some examples:

- German: Normalize “ß” to “ss” only if needed; it changes spelling.

- Turkish: Dotless/i-dotted

I/ı/İ behave differently with basic .lower().

- Chinese/Japanese: Full-width vs half-width characters; punctuation and numerals can have multiple forms.

- Arabic: Diacritics, multiple forms of

alef, etc.

For multilingual text, consider using language detection and applying language-specific normalization steps.

# pseudo-code

if lang == "de":

text = german_normalize(text)

elif lang == "tr":

text = turkish_case_normalize(text)

6. Tokenization: Splitting Text into Units

After cleaning and normalization, you’re ready for tokenization: splitting text into pieces your model understands.

6.1 Types of Tokenization

| Type |

Example |

Pros |

Cons |

| Whitespace |

"hello world" → ["hello", "world"] |

Simple, fast |

Fails on punctuation, languages without spaces |

| Rule-based |

Uses regex / language rules |

Better word boundaries |

Still brittle for noisy text |

| Wordpiece / BPE |

"playing" → ["play", "##ing"] |

Handles OOV, compact vocab |

More complex, needs pre-trained vocab |

| Character |

"play" → ["p","l","a","y"] |

No OOV, language-agnostic |

Longer sequences, less semantic info |

The right choice depends on:

- Model architecture (classic ML vs transformer)

- Language(s) involved

- Task (classification, generation, retrieval)

6.2 Simple Whitespace + Punctuation Tokenization

For quick classic ML baselines (e.g., Naive Bayes, SVM), a basic tokenizer might be enough:

import re

TOKEN_RE = re.compile(r"\w+|[^\w\s]", re.UNICODE)

def simple_tokenize(text: str):

return TOKEN_RE.findall(text)

text = "Hello, world! It's 2024."

print(simple_tokenize(text))

# ['Hello', ',', 'world', '!', 'It', "'", 's', '2024', '.']

Typically you’d post-process contractions (“It’s” → ["It's"]) or use libraries like spaCy or NLTK:

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("Hello, world! It's 2024.")

print([token.text for token in doc])

# ['Hello', ',', 'world', '!', 'It', "'s", '2024', '.']

6.3 Subword Tokenization (BPE / WordPiece)

Most modern transformer models (BERT, RoBERTa, GPT variants) use subword tokenization to handle rare words and misspellings.

Example with Hugging Face transformers:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("bert-base-uncased")

text = "Tokenization is crucial for NLP models."

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(text)

ids = tokenizer.encode(text, add_special_tokens=True)

print(tokens)

print(ids)

print(tokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens(ids))

You typically should not roll your own tokenizer when using a pre-trained transformer. Use the tokenizer associated with that model; it encapsulates crucial assumptions:

- Vocabulary and ID mapping

- Special tokens ([CLS], [SEP], [PAD])

- Pre-tokenization (spacing, punctuation handling)

6.4 Character-Level Tokenization

Character-level tokenization is useful when:

- You expect lots of typos / noisy text (user input, OCR).

- You work with many languages or scripts.

- You’re building models that learn morphology from scratch.

def char_tokenize(text: str):

return list(text)

print(char_tokenize("Hello!"))

# ['H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '!']

Sequence length grows and training becomes more expensive, but you get robustness to OOV words.

7. Putting It Together: A Reusable Preprocessing Pipeline

Let’s assemble the pieces into a reusable preprocessing function for a typical English text classification task using BERT:

7.1 Designing the Pipeline

We’ll combine:

- Unicode normalization

- Optional case normalization (for non-cased models)

- HTML stripping

- Noise removal (URLs, emails, mentions)

- Whitespace normalization

- Tokenization via pre-trained tokenizer

import re

import unicodedata

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

URL_RE = re.compile(r"https?://\S+|www\.\S+")

EMAIL_RE = re.compile(r"\b[\w\.-]+@[\w\.-]+\.\w+\b")

MENTION_RE = re.compile(r"@\w+")

WS_RE = re.compile(r"\s+")

def strip_html(text: str) -> str:

soup = BeautifulSoup(text, "lxml")

return soup.get_text(separator=" ", strip=True)

def normalize_unicode(text: str) -> str:

return unicodedata.normalize("NFKC", text)

def remove_noise(text: str) -> str:

text = URL_RE.sub(" <URL> ", text)

text = EMAIL_RE.sub(" <EMAIL> ", text)

text = MENTION_RE.sub(" <USER> ", text)

return text

def normalize_whitespace(text: str) -> str:

text = text.strip()

text = WS_RE.sub(" ", text)

return text

class TextPreprocessor:

def __init__(self, model_name: str = "bert-base-uncased"):

self.tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

self.lowercase = "uncased" in model_name

def clean_text(self, text: str) -> str:

text = normalize_unicode(text)

text = strip_html(text)

text = remove_noise(text)

text = normalize_whitespace(text)

if self.lowercase:

text = text.lower()

return text

def encode(self, text: str, max_length: int = 128):

cleaned = self.clean_text(text)

encoded = self.tokenizer(

cleaned,

padding="max_length",

truncation=True,

max_length=max_length,

return_tensors="pt",

)

return encoded, cleaned

# Usage

preprocessor = TextPreprocessor("bert-base-uncased")

encoded, cleaned_text = preprocessor.encode("<p>Hello WORLD!!! Visit: https://example.com</p>")

print(cleaned_text)

# hello world!!! visit: <url>

print(encoded["input_ids"].shape) # torch.Size([1, 128])

This gives you:

- A cleaned text representation (useful for debugging and inspection).

- A tokenized+encoded representation ready for model input.

The preprocessing steps differ depending on the model type.

| Step |

Classic ML (SVM, NB) |

Transformers (BERT, RoBERTa) |

| Lowercasing |

Common, often beneficial |

Follow model’s cased/uncased setting |

| Stopword removal |

Often used (e.g., TF-IDF) |

Usually not needed; can hurt understanding |

| Stemming / Lemmatization |

Common for generalization |

Rarely used; can break learned token statistics |

| Subword tokenization |

Rare |

Standard, use model’s tokenizer |

| Vocabulary size |

Can be large (50k–200k) |

Typically 30k–50k shared subword vocab |

When using transformers, avoid heavy-handed preprocessing like stemming or aggressive stopword removal. These models are trained on raw-ish text and rely on all tokens to understand context.

9. Handling Special Cases

9.1 Emojis and Emoticons

Emojis can be very informative, especially for sentiment tasks.

You can:

- Map emojis to textual descriptions (e.g., ???? → “smiling_face”).

- Leave them in and let the model handle them (transformers often can).

import emoji

def demojize(text: str) -> str:

# :) ???? → :slightly_smiling_face: :thumbs_up:

return emoji.demojize(text, delimiters=(" ", " "))

print(demojize("I love this! ????????"))

# I love this! smiling_face_with_heart_eyes thumbs_up

9.2 Numbers

Depending on the task:

- Keep exact numbers (e.g., price prediction).

- Normalize to a placeholder (e.g.,

<NUM>) if only magnitude/presence matters.

NUM_RE = re.compile(r"\b\d+(\.\d+)?\b")

def normalize_numbers(text: str) -> str:

return NUM_RE.sub(" <NUM> ", text)

9.3 Code Snippets in Text

If you’re processing developer conversations (issue trackers, docs, Q&A), code is often signal, not noise. You might:

- Extract code blocks separately.

- Replace code with placeholders while preserving labels.

- Use specialized tokenizers for code (e.g., tree-sitter or model-specific tokenizers) in parallel.

10. Practical Tips and Gotchas

10.1 Don’t Over-Clean

Overzealous cleaning can hurt model performance:

- Removing punctuation can confuse sentence boundaries.

- Removing stopwords can break grammar and context.

- Normalizing too aggressively can erase distinctions important to your task.

A sanity-check strategy:

- Apply your pipeline to 20–50 random examples.

- Inspect raw vs cleaned side-by-side.

- Adjust rules until cleaned text looks “reasonable” for your use case.

10.2 Log and Version Your Preprocessing

Preprocessing is part of the model. If you change it, your model behaves differently.

Good practices:

- Encapsulate preprocessing in a class/module.

- Version your preprocessing code separately.

- Log the preprocessing version used for each trained model.

- For online inference, ensure you use the exact same pipeline as training.

10.3 Language and Domain Drift

If your model will be used over time:

- Monitor input distribution (length, language, presence of new tokens).

- New slang, emojis, or jargon may require adjusting tokenization or normalization.

- Consider periodic vocab extension or fine-tuning.

11. Example: End-to-End Mini Project

Let’s tie this together with a simple sentiment classification example.

11.1 Dataset and Goal

Suppose you have a CSV:

text,label

"I love this product!!! :)",positive

"Terrible quality, do not buy.",negative

...

You want to build a BERT-based classifier.

11.2 Preprocessing + Dataset

import torch

from torch.utils.data import Dataset, DataLoader

import pandas as pd

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

class SentimentDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, csv_path: str, model_name: str = "bert-base-uncased", max_length: int = 128):

self.df = pd.read_csv(csv_path)

self.tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

self.max_length = max_length

self.label2id = {"negative": 0, "positive": 1}

def __len__(self):

return len(self.df)

def __getitem__(self, idx):

row = self.df.iloc[idx]

text = row["text"]

# basic normalization, you can reuse the TextPreprocessor from above

text = unicodedata.normalize("NFKC", text)

text = text.strip()

encoded = self.tokenizer(

text,

padding="max_length",

truncation=True,

max_length=self.max_length,

return_tensors="pt",

)

label = self.label2id[row["label"]]

return {

"input_ids": encoded["input_ids"].squeeze(0),

"attention_mask": encoded["attention_mask"].squeeze(0),

"label": torch.tensor(label, dtype=torch.long),

}

dataset = SentimentDataset("sentiment.csv")

loader = DataLoader(dataset, batch_size=16, shuffle=True)

batch = next(iter(loader))

print(batch["input_ids"].shape, batch["label"].shape)

# torch.Size([16, 128]) torch.Size([16])

Here we leaned on the model’s tokenizer and kept preprocessing minimal, which is usually a good starting point with transformers.

12. Summary and Key Takeaways

Preparing raw text for NLP models is not glamorous, but it’s where a lot of model quality is won or lost.

Key points:

-

Inspect before you clean

Understand your data: encoding issues, HTML, duplicates, noise.

-

Clean selectively, not blindly

Remove clear noise (HTML, boilerplate, extraneous logs) while preserving task-relevant signal (emojis, code, punctuation).

-

Normalize for consistency

- Unicode normalization (NFC/NFKC)

- Well-considered casing (especially for cased vs uncased models)

- Whitespace and punctuation handling

-

Tokenization should match your model

- Classic ML: simple word-level tokenization, possibly with stopword removal and lemmatization.

- Transformers: use the provided subword tokenizer; avoid heavy preprocessing that deviates from pretraining.

-

Keep preprocessing reproducible and versioned

Treat your preprocessing pipeline as part of your model’s contract. Any change should be deliberate and traceable.

-

Use simple tools to help with manual steps

When preparing rule lists, small corpora, or debugging, utilities like the htcUtils Case Converter and htcUtils Text Sorter & Cleaner can speed up manual normalization, case transformations, and line-level cleaning outside of code.

With a robust, thoughtfully designed text preparation pipeline, your NLP experiments will be more stable, interpretable, and effective—and you’ll spend less time chasing weird edge cases and data bugs.