Audio bytes are only half the story. For most real-world applications—music players, podcast apps, asset pipelines, archives—metadata is what makes audio discoverable, sortable, and usable.

This guide walks through how audio metadata actually works: schemas, tagging standards, container formats, and practical workflows for reading, writing, and validating tags across common formats like MP3, FLAC, WAV, AAC, and more.

If you’re building a media app, audio pipeline, or anything that touches sound files at scale, understanding this ecosystem will save you a lot of pain.

Audio metadata is information about an audio file that isn’t the raw waveform:

- Track title, artist, album

- Track number, disc number

- Genre, year, composer

- ReplayGain / loudness info

- ISRC, UPC, catalog numbers

- Embedded artwork

- Lyrics, comments, subtitles

- Technical attributes (bitrate, sample rate)

What makes it messy:

- Multiple standards: ID3, Vorbis Comments, RIFF INFO, APE tags, MP4 atoms, etc.

- Multiple containers: MP3, FLAC, WAV, AIFF, Ogg, MP4, etc.—each with specific tagging rules.

- Multiple schemas: Different fields and naming conventions (

TRACKNUMBER vs TRCK, ALBUMARTIST vs TPE2).

- Real-world chaos: Badly tagged files, inconsistent casing, missing encodings.

Your job as a developer is often to bridge these differences in a consistent model your app understands.

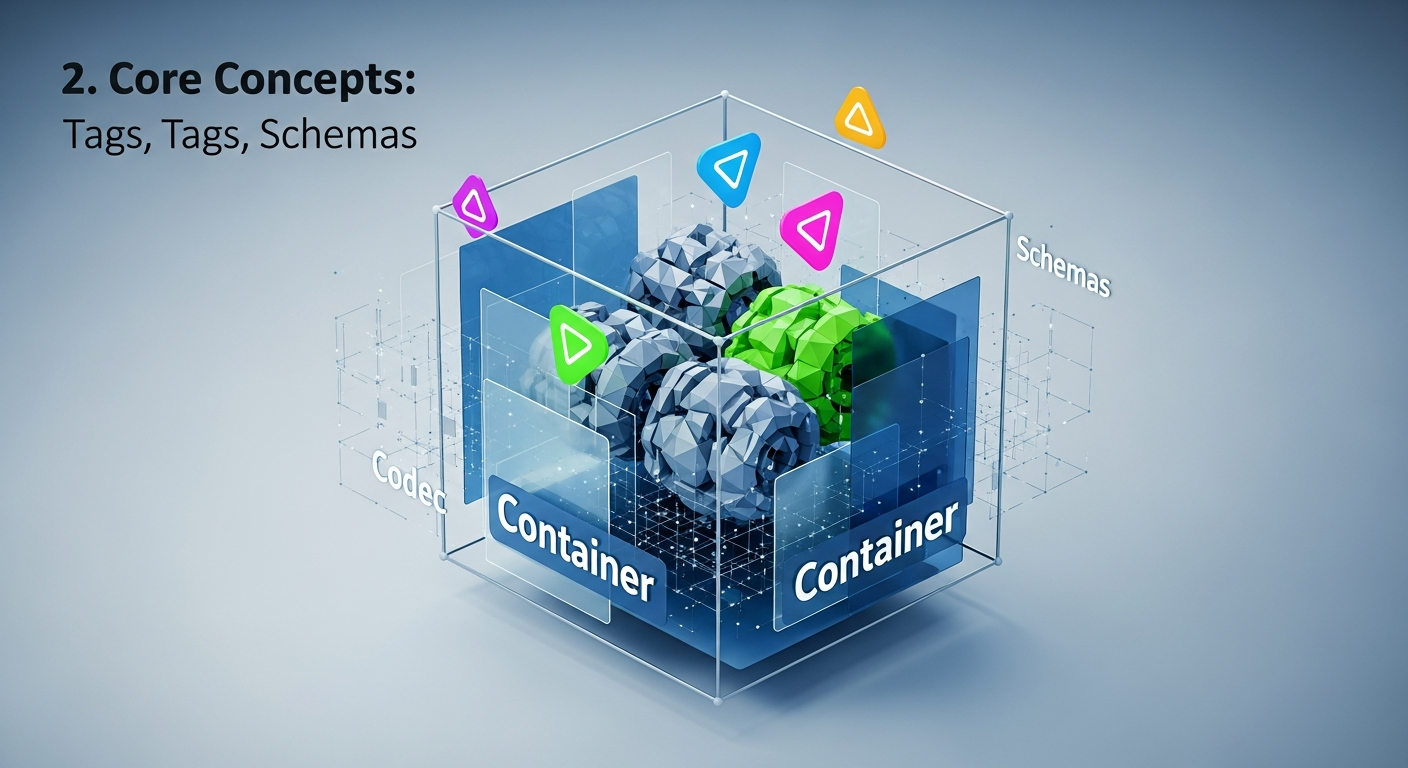

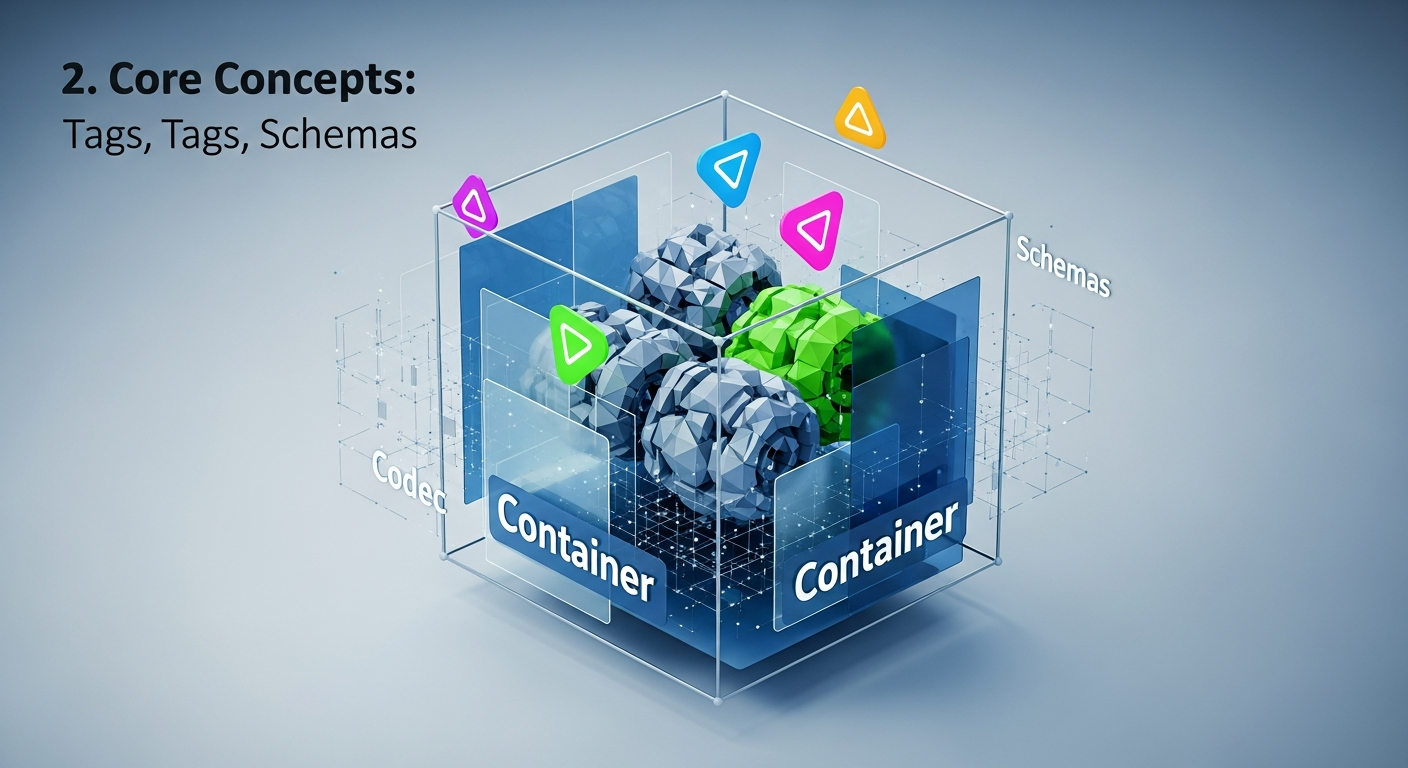

Before we dive into specific formats, it helps to separate a few concepts developers often conflate:

| Concept |

Examples |

What it is |

| Container |

MP3, FLAC, WAV, Ogg, MP4, M4A |

File wrapper; defines how audio data and metadata are stored |

| Codec |

MP3, AAC, FLAC, Opus, PCM |

Compression algorithm used to encode the audio data |

| Tag format |

ID3, Vorbis Comments, APE, RIFF INFO, MP4 atoms |

The structure used to store metadata within the container |

| Schema |

“title, artist, album, track…” |

The conceptual set of metadata fields and their meanings |

For example:

- A

.flac file → container: FLAC, codec: FLAC, tags: Vorbis Comments.

- A

.m4a file → container: MP4, codec: AAC or ALAC, tags: MP4 atoms (©nam, ©ART, etc.).

- A

.mp3 file → container: MP3, codec: MP3, tags: typically ID3v2 + optional ID3v1/APE.

Different standards describe similar concepts with different names. Here’s a minimal cross-format schema many apps use:

| Logical Field |

Typical ID3 Frame |

Vorbis Comment Key |

MP4 Atom |

Notes |

| Title |

TIT2 |

TITLE |

©nam |

|

| Artist |

TPE1 |

ARTIST |

©ART |

Track-level performer |

| Album |

TALB |

ALBUM |

©alb |

|

| Album Artist |

TPE2 |

ALBUMARTIST |

aART |

Important for compilations |

| Track Number |

TRCK |

TRACKNUMBER |

trkn |

Often “x” or “x/y” |

| Disc Number |

TPOS |

DISCNUMBER |

disk |

Likewise “d” or “d/n” |

| Year/Date |

TDRC / TYER |

DATE |

©day |

ID3 has multiple date frames |

| Genre |

TCON |

GENRE |

©gen |

ID3 supports numeric genres |

| Comment |

COMM |

COMMENT |

©cmt |

Semantics vary |

| Composer |

TCOM |

COMPOSER |

©wrt |

|

| Album Art |

APIC |

METADATA_BLOCK_PICTURE |

covr |

Binary image data |

| ISRC |

TSRC |

ISRC |

— or ----:com.apple.iTunes:ISRC |

Track identifier |

Designing your system around a logical schema and then mapping to/from each tag format is usually the best strategy.

4.1 ID3 (Mostly for MP3)

ID3 is the dominant tag format for MP3 and is occasionally used in other containers.

- ID3v1: Very old, fixed-size, 128 bytes at file end. Severely limited fields and character set.

- ID3v2: Flexible, extensible, located at the beginning of the file. Multiple minor versions: v2.2, v2.3, v2.4.

Typical ID3v2 structure:

[ID3 header][frames...][padding][audio data...]

Each frame has:

- A frame ID (e.g.,

TIT2, TPE1)

- Size

- Flags

- Data (often starting with text encoding byte)

Reading ID3 in Python

from mutagen.id3 import ID3

tags = ID3("song.mp3")

title = tags.get("TIT2")

artist = tags.get("TPE1")

album = tags.get("TALB")

print("Title:", title.text[0] if title else None)

print("Artist:", artist.text[0] if artist else None)

print("Album:", album.text[0] if album else None)

Practical tips for ID3

- Support both v2.3 and v2.4 if possible. Many tools still write v2.3.

- Handle encoding issues (UTF-16 vs Latin-1 vs UTF-8).

- Normalize genres (ID3 allows numeric codes and free text).

- Prefer v2 tags over legacy v1 tags when both exist.

Vorbis Comments are used by:

- FLAC (

.flac)

- Ogg Vorbis (

.ogg)

- Ogg Opus (

.opus)

Unlike ID3, Vorbis Comments:

- Use simple key=value pairs

- Are UTF-8 encoded

- Are mostly free-form but with some conventions

Example from a FLAC file:

TITLE=My Song

ARTIST=Some Artist

ALBUM=Cool Album

TRACKNUMBER=3

DISCNUMBER=1

ALBUMARTIST=Various Artists

from mutagen.flac import FLAC

audio = FLAC("track.flac")

print(audio.get("title")) # ['My Song']

print(audio.get("artist")) # ['Some Artist']

print(audio.get("tracknumber")) # ['3']

Practical tips for Vorbis/FLAC

- Keys are technically case-insensitive, but typical conventions use uppercase in specs and mixed case in tools.

- Multi-value fields (like multiple artists) are often stored as repeated keys or separated by

; or ,. You’ll need your own normalization rules.

- FLAC album art isn’t stored as a Vorbis comment; it uses a PICTURE metadata block or

METADATA_BLOCK_PICTURE base64 in a comment.

4.3 RIFF/INFO & Broadcast WAV (WAV, AIFF)

Plain WAV files (RIFF containers) and AIFF often carry metadata in RIFF INFO chunks or specialized chunks like LIST, ID3, iXML, bext (Broadcast Extension).

Common RIFF INFO tags:

| Field |

Meaning |

INAM |

Title |

IART |

Artist |

IPRD |

Product/Album |

ICRD |

Creation date |

ICMT |

Comment |

Broadcast WAV (BWF) adds bext, iXML, and others for professional workflows (broadcast, film, etc.) with rich metadata like timecodes, origination, and usage rights.

- Many WAVs have no metadata at all.

- There’s no widely enforced standard for rich tag sets like modern music players expect.

- You may also find embedded ID3 chunks in WAV files.

4.4 MP4/QuickTime Atoms (AAC, ALAC, M4A)

AAC/ALAC/M4A files (MP4 container) store metadata in atoms (boxes) nested inside the file.

Music metadata lives mostly in the moov → udta → meta → ilst atoms, where each field has a 4-character code:

©nam – title©ART – artistaART – album artist©alb – albumtrkn – track numberdisk – disc number©day – release date©gen – genrecovr – cover art

from mutagen.mp4 import MP4

audio = MP4("track.m4a")

print(audio.tags.get("\xa9nam")) # Title

print(audio.tags.get("\xa9ART")) # Artist

print(audio.tags.get("aART")) # Album artist

print(audio.tags.get("trkn")) # Track number ([(track, total_tracks)])

Practical tips for MP4

- Many fields use proprietary codes, especially from iTunes (

----:com.apple.iTunes:…).

trkn and disk are typically arrays of tuples: [(track, total)], [(disc, total_discs)].- Artwork in

covr can contain multiple images and may be PNG or JPEG.

APE tags are used in:

- Monkey’s Audio (

.ape)

- Sometimes in MP3/other files as an alternative tag system.

They’re key=value like Vorbis Comments but with their own structure and often used for:

- Lossless formats

- ReplayGain

- Niche use cases

Support for APE tags is more limited than ID3/Vorbis/MP4, but you’ll encounter them if you handle large legacy libraries.

5. Common Audio Containers and Their Tagging Systems

Here’s a summary of common containers and what tagging systems they typically use:

| Container |

File Extensions |

Typical Codec(s) |

Typical Tag Format |

| MP3 |

.mp3 |

MP3 |

ID3v2 (+ optional ID3v1, APE) |

| FLAC |

.flac |

FLAC |

Vorbis Comments + FLAC blocks |

| Ogg Vorbis |

.ogg |

Vorbis |

Vorbis Comments |

| Ogg Opus |

.opus |

Opus |

Vorbis Comments |

| WAV |

.wav |

PCM, others |

RIFF INFO, BWF, iXML, possibly ID3 |

| AIFF |

.aiff, .aif |

PCM |

IFF chunks (similar to RIFF) |

| MP4/M4A |

.mp4, .m4a |

AAC, ALAC |

MP4 atoms (QuickTime-style) |

| WMA |

.wma |

WMA |

ASF metadata |

| APE |

.ape |

Monkey’s Audio |

APE tags |

When designing your metadata layer, it’s useful to think of it as:

flowchart LR

subgraph App

A[App Metadata Model]

end

B[MP3] -->|ID3| A

C[FLAC] -->|Vorbis Comments| A

D[Ogg/Opus] -->|Vorbis Comments| A

E[MP4/M4A] -->|MP4 Atoms| A

F[WAV/AIFF] -->|RIFF/Other| A

A -->|write| B

A -->|write| C

A -->|write| D

A -->|write| E

A -->|write| F

Your app defines a canonical model and you map to/from each format’s native tags.

6.1 Unified Access in Python with mutagen

mutagen is a good Python library for abstracting over multiple formats.

from mutagen import File

def get_basic_tags(path: str):

audio = File(path, easy=True)

if audio is None:

raise ValueError(f"Unsupported or invalid audio file: {path}")

# Easy tags gives approx. format-independent keys

return {

"title": (audio.get("title") or [None])[0],

"artist": (audio.get("artist") or [None])[0],

"album": (audio.get("album") or [None])[0],

"track": (audio.get("tracknumber") or [None])[0],

"disc": (audio.get("discnumber") or [None])[0],

"albumartist": (audio.get("albumartist") or [None])[0],

}

tags = get_basic_tags("example.flac")

print(tags)

Always:

- Read existing tags.

- Update or add.

- Save.

- Optionally validate the result.

Example: setting title and artist for a FLAC file:

from mutagen.flac import FLAC

def set_flac_tags(path, title=None, artist=None):

audio = FLAC(path)

if title is not None:

audio["title"] = title

if artist is not None:

audio["artist"] = artist

audio.save()

set_flac_tags("track.flac", title="New Title", artist="New Artist")

You’ll often want a unified representation like:

{

"title": "Song Name",

"artist": "Artist Name",

"album": "Album Name",

"albumArtist": "Album Artist",

"trackNumber": 3,

"trackTotal": 12,

"discNumber": 1,

"discTotal": 2,

"year": 2023,

"genre": "Rock",

"isrc": "USABC1234567"

}

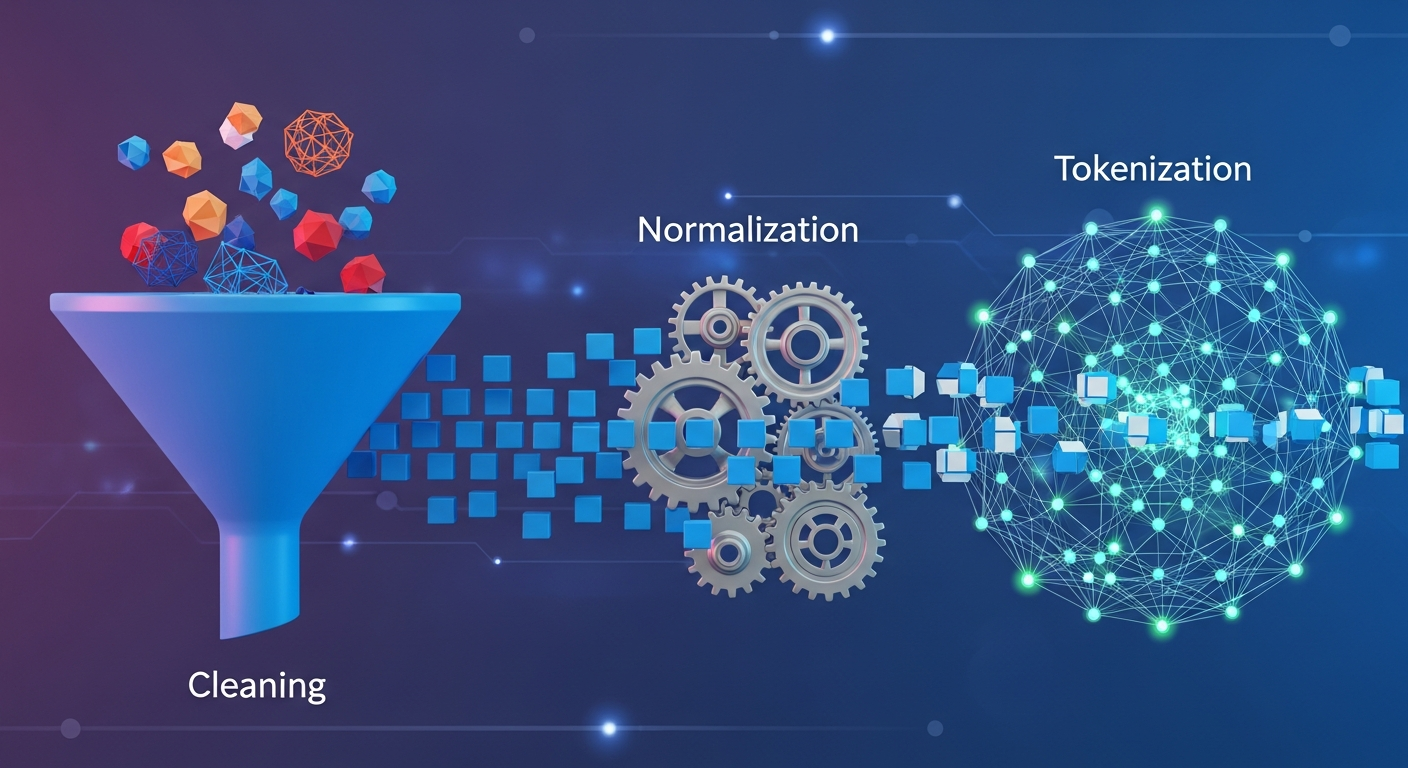

The challenge is mapping:

- MP3 (ID3

TRCK = 3/12) → trackNumber=3, trackTotal=12

- FLAC (Vorbis

TRACKNUMBER=3, TOTALTRACKS=12) → same logical fields

- MP4 (

trkn=[(3, 12)]) → same again

7.1 Example Mapping Function (Pseudo-Python)

def parse_track_field(value: str | None):

# Handles "3", "3/12", etc.

if not value:

return None, None

parts = value.split("/")

track = int(parts[0]) if parts[0].isdigit() else None

total = int(parts[1]) if len(parts) > 1 and parts[1].isdigit() else None

return track, total

Then, per format, you interpret the raw tags into your normalized schema. For bulk libraries, this normalization step becomes an essential part of your import pipeline.

8. Validation, Integrity, and Troubleshooting

Because metadata standards are loosely enforced in the wild, validation is key:

- Detect missing critical fields (

title, artist, album).

- Check for inconsistent types (e.g., non-numeric

TRACKNUMBER).

- Verify embedded artwork is within size limits and correct format.

- Confirm encoding is valid and no invalid characters are present.

When you’re dealing with large collections, it’s helpful to quickly inspect metadata for issues. For that, tools like the Audio Metadata Checker (audio) can be handy to visually inspect and debug tags across different formats without writing a custom script for every small check.

8.1 Common Real-World Problems

- Duplicate tags: ID3v1 + ID3v2; tools may show one and ignore the other.

- Wrong encodings: Latins characters misread due to incorrect encoding declarations.

- Inconsistent album artist: Compilation albums where some tracks have

Various Artists and others have specific artists as album artist.

- Track numbers without totals:

3 vs 3/12 vs 03.

- Multiple tag systems in one file: e.g., APE + ID3 on MP3; some players prefer one, others the opposite.

9. Best Practices for Developers

9.1 Design a Clear Internal Schema

Define your own internal metadata model and keep it stable:

- Decide which fields you care about (title, artist, album, etc.).

- Standardize types (e.g.,

trackNumber as integer, year as integer).

- Keep the mapping to/from each tag format in one place in your codebase.

When importing:

- Normalize string casing and whitespace.

- Convert numbers to integers where appropriate.

- Split and interpret fields like

TRACKNUMBER, DISCNUMBER.

- If multiple tags disagree (e.g., ID3v1 vs v2), select a priority source.

9.3 Preserve Unknown Data

Even if your app doesn’t use some tags, avoid deleting them:

- Read all tags.

- Modify only the fields you care about.

- Write back preserving the rest.

Users may depend on tags your app doesn’t know about (e.g., DJ software fields, ReplayGain).

9.4 Handle Artwork Carefully

- Keep image size reasonable (e.g., ≤ 1000x1000 or 1500x1500 for most use cases).

- Support both JPEG and PNG where the format allows it (MP4, ID3 APIC).

- Avoid embedding massive 10MB artwork in every file if disk or bandwidth matters.

Reading artwork with mutagen (MP3 example):

from mutagen.id3 import ID3, APIC

tags = ID3("song.mp3")

for frame in tags.getall("APIC"):

print("MIME type:", frame.mime)

print("Description:", frame.desc)

image_data = frame.data # bytes: write to file or process

To tie this together, here’s a minimal CLI example in Python that prints basic tags for a file using mutagen:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sys

from mutagen import File

def print_tags(path: str):

audio = File(path, easy=True)

if audio is None:

print(f"Unsupported or invalid audio file: {path}")

return

basic_fields = ["title", "artist", "album", "albumartist", "tracknumber", "discnumber", "date", "genre"]

print(f"Metadata for: {path}")

for field in basic_fields:

value = audio.get(field)

if value:

# mutagen's easy tags usually give lists

print(f"{field}: {', '.join(value)}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

print("Usage: meta-info.py <audio-file>")

sys.exit(1)

print_tags(sys.argv[1])

Run:

python meta-info.py song.mp3

This is a good base you can extend with writing, normalization, and bulk processing.

11. Summary: Key Takeaways

- Audio metadata is fragmented: multiple tag formats (ID3, Vorbis, MP4 atoms, RIFF INFO) across different containers.

- Think in schemas: Define a format-agnostic internal metadata model and map to/from each file format.

- ID3, Vorbis, MP4 atoms, and RIFF cover most real-world audio tagging needs.

- Validation and normalization are essential for dealing with real-world libraries.

- Preserve unknown tags and be careful when rewriting files to avoid data loss.

- Testing across formats (MP3, FLAC, WAV, M4A, Ogg) reveals edge cases you won’t see if you only test on one.

Once you internalize how these metadata systems fit together, building robust audio workflows—players, tag editors, media servers, batch processors—becomes much more predictable and less mysterious.