Complete Guide to Secure Password Storage: Hashing, Salting, and Peppering Explained

Passwords are still the most common authentication mechanism on the web. That also makes them one of the biggest attack targets. As developers, we have a responsibility: even if users choose weak passwords, our systems must store them as safely as possible.

This guide walks through hashing, salting, and peppering—what they are, why you need all three, and how to implement them correctly with real-world examples and patterns.

We’ll cover:

- Why plaintext password storage is catastrophic

- The difference between hashing, salting, and peppering

- How modern password-hashing functions (bcrypt, Argon2, scrypt, PBKDF2) actually work

- Practical implementation examples (Node.js, Python)

- Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- How to help users choose strong passwords in the first place

1. The Goal: What “Secure Password Storage” Actually Means

Before we dive into terminology, it helps to define the goal.

When you store passwords securely:

- An attacker who dumps your database should not be able to:

- Read plaintext passwords

- Quickly guess weak passwords at scale

- The cost of cracking a single password must be high enough to:

- Make large-scale cracking impractical

- Buy you enough time to respond (rotate keys, notify users, etc.)

In practice, this means:

- Never storing plaintext passwords

- Never storing encrypted passwords with reversible keys in the same system

- Using slow, memory-hard password hashing functions

- Adding per-user randomness (salt)

- Optionally adding a secret key (pepper) stored separately from the DB

2. Hashing, Salting, Peppering: Quick Definitions

Let’s clarify terminology first, then we’ll dig into details.

| Concept |

Stored in DB? |

Purpose |

Secret? |

| Hash |

Yes |

Irreversibly transform password |

No |

| Salt |

Yes |

Make hashes unique per user; defeat rainbow tables |

No |

| Pepper |

No (ideally) |

Add secret server-side key to make offline cracking harder |

Yes |

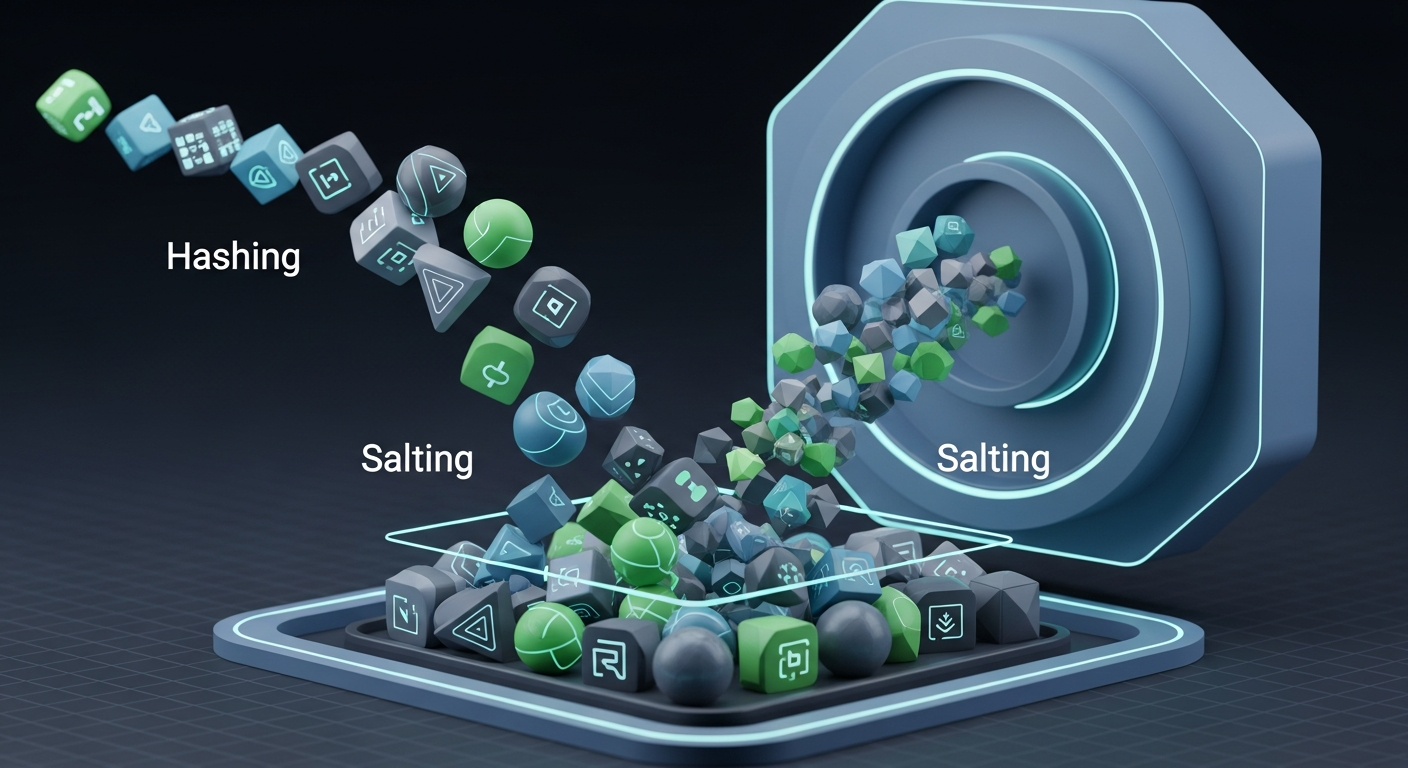

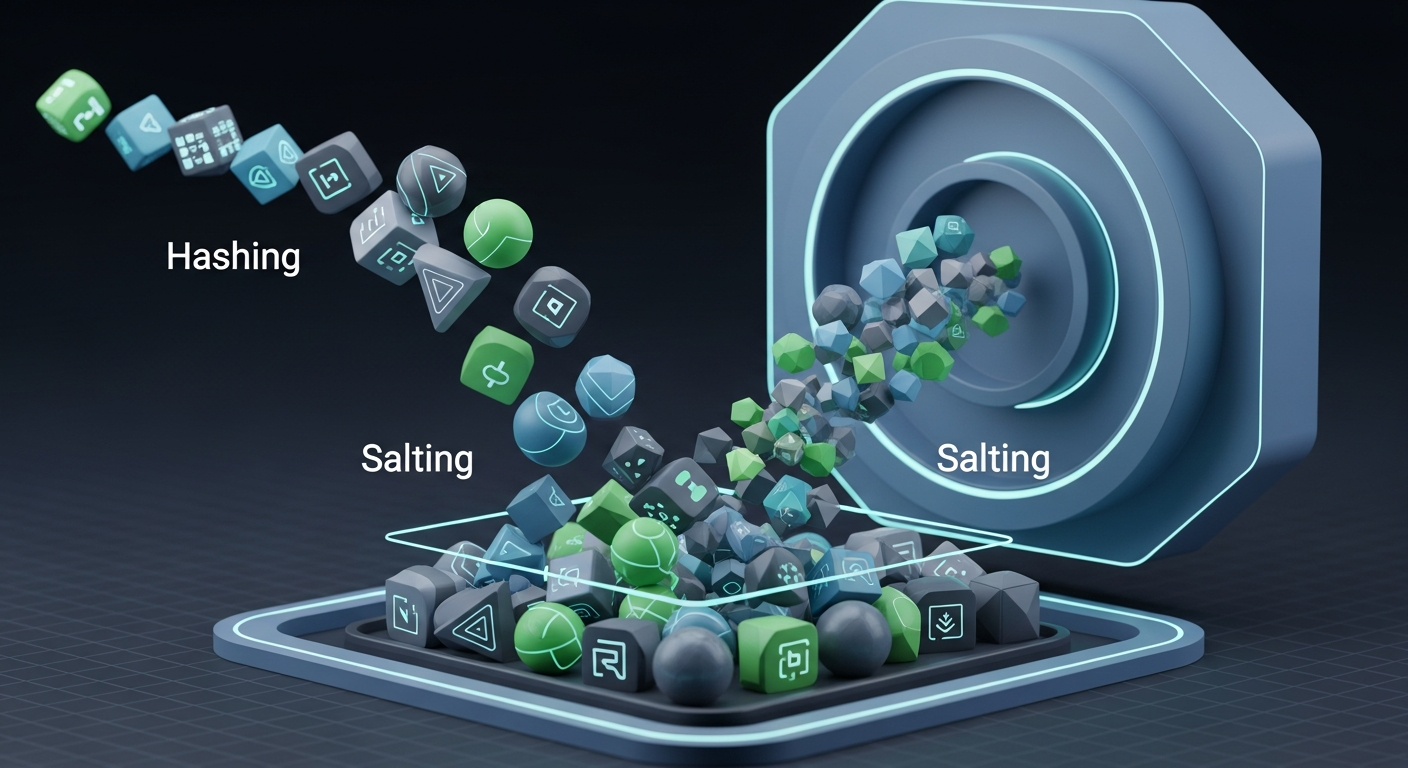

2.1 Hashing

A hash function maps input data (like a password) to a fixed-length output:

password -> hash(password) -> "e3b0c44298fc1c149afbf4c8996fb..."

Properties we want for password hashing:

- One-way: You can’t recover the password from the hash

- Collision-resistant: Different passwords rarely produce the same hash

- Deliberately slow: To make brute-force attacks expensive

Important: regular hash functions like SHA-256 and SHA-512 are cryptographically secure for integrity, but too fast for password hashing. Attackers can compute billions per second on GPUs.

2.2 Salting

A salt is a random value generated per user (or per password) and stored alongside the hash.

Instead of:

hash = H(password)

We compute:

hash = H(password + salt)

Salting ensures:

- Two users with the same password get different hashes

- Precomputed rainbow tables become useless

- Attacks must be done on each hash individually

2.3 Peppering

A pepper is similar to a salt but:

- It is secret

- It is shared across many passwords (typically system-wide)

- It is not stored in the database

Instead of:

hash = H(password + salt)

we can do:

hash = H(password + salt + pepper)

If an attacker steals your database but not your config/secrets store (where the pepper lives), cracking passwords becomes significantly harder.

3. Password Hashing Algorithms: What You Should Use Today

Don’t roll your own hashing algorithm. Use a battle-tested password hashing function designed for this exact purpose.

Common choices:

| Algorithm |

Properties |

Notes |

| bcrypt |

Slow, CPU-bound |

Very widely used; limited to 72-byte passwords |

| Argon2id |

Slow, memory-hard |

Winner of Password Hashing Competition; recommended modern choice |

| scrypt |

Memory-hard |

Good but slightly older than Argon2 |

| PBKDF2 |

Iteration-based |

Still acceptable, widely supported, but weaker against GPUs than Argon2/scrypt |

For new applications, Argon2id is usually the best default if your language ecosystem supports it.

4. The Secure Password Storage Flow

Here’s the high-level flow when a user signs up and logs in.

sequenceDiagram

participant U as User

participant A as App Server

participant D as Database

participant S as Secret Store (Pepper)

U->>A: Signup / Register (username + password)

A->>A: Generate random salt

A->>S: Load pepper (secret)

A->>A: Derive hash = HashFn(password, salt, pepper)

A->>D: Store { username, salt, hash, algorithm params }

U->>A: Login (username + password)

A->>D: Load user record (salt, hash, params)

A->>S: Load pepper

A->>A: Compute hash' = HashFn(password, stored salt, pepper)

A->>A: Compare hash' with stored hash (constant-time)

A-->>U: Success or failure

5. Practical Implementation: Hashing + Salting

Let’s walk through an example using bcrypt and Argon2.

5.1 Node.js Example (bcrypt)

// npm install bcrypt

const bcrypt = require('bcrypt');

const BCRYPT_ROUNDS = 12; // Adjust for your hardware

async function hashPassword(plainPassword) {

const salt = await bcrypt.genSalt(BCRYPT_ROUNDS);

const hash = await bcrypt.hash(plainPassword, salt);

// bcrypt embeds the salt and cost in the hash string

return hash; // e.g. "$2b$12$...."

}

async function verifyPassword(plainPassword, storedHash) {

return bcrypt.compare(plainPassword, storedHash);

}

// Usage

(async () => {

const password = 'MySuperSecretPassword123!';

const hash = await hashPassword(password);

console.log('Hash:', hash);

const ok = await verifyPassword(password, hash);

console.log('Password valid?', ok);

})();

With bcrypt, the salt is embedded inside the hash string. You don’t store the salt separately; the library manages it.

5.2 Python Example (Argon2)

# pip install argon2-cffi

from argon2 import PasswordHasher

# Argon2 parameters – tune for your environment

ph = PasswordHasher(

time_cost=3, # number of iterations

memory_cost=65536, # in KiB (64 MB)

parallelism=4,

)

def hash_password(plain_password: str) -> str:

return ph.hash(plain_password)

def verify_password(plain_password: str, stored_hash: str) -> bool:

try:

ph.verify(stored_hash, plain_password)

return True

except Exception:

return False

# Usage

if __name__ == "__main__":

password = "MySuperSecretPassword123!"

hashed = hash_password(password)

print("Hash:", hashed)

print("Valid?", verify_password(password, hashed))

Argon2 also encodes its parameters (time, memory, parallelism, salt) inside the hash string.

6. Adding Peppering Safely

Peppering adds an extra layer of defense by introducing a server-side secret.

6.1 Where to Store the Pepper

Do not store the pepper in:

- The database (defeats the purpose)

- Version control (e.g., committed to Git)

Better options:

- Environment variables (for smaller setups)

- A secrets manager (e.g., HashiCorp Vault, cloud provider secret stores)

- A hardware security module (HSM) for very sensitive systems

6.2 Example: Node.js + bcrypt + Pepper

const bcrypt = require('bcrypt');

const BCRYPT_ROUNDS = 12;

const PEPPER = process.env.PASSWORD_PEPPER; // from env or secret store

async function hashPassword(plainPassword) {

const salt = await bcrypt.genSalt(BCRYPT_ROUNDS);

const hash = await bcrypt.hash(plainPassword + PEPPER, salt);

return hash;

}

async function verifyPassword(plainPassword, storedHash) {

return bcrypt.compare(plainPassword + PEPPER, storedHash);

}

6.3 Example: Python + Argon2 + Pepper

import os

from argon2 import PasswordHasher

ph = PasswordHasher(

time_cost=3,

memory_cost=65536,

parallelism=4,

)

PEPPER = os.environ.get("PASSWORD_PEPPER", "")

def hash_password(plain_password: str) -> str:

return ph.hash(plain_password + PEPPER)

def verify_password(plain_password: str, stored_hash: str) -> bool:

try:

ph.verify(stored_hash, plain_password + PEPPER)

return True

except Exception:

return False

With peppering:

- A database leak alone is less catastrophic

- The attacker also needs access to your secret management layer

7. Why Simple Hashing (without Salt/Pepper) Is Dangerous

Consider this naive approach:

const crypto = require('crypto');

function insecureHashPassword(password) {

// ❌ Do NOT do this

return crypto.createHash('sha256').update(password).digest('hex');

}

Problems:

-

No salt

- Two users with the same password get the same hash

- Rainbow table attacks become trivial

-

Fast hash function

- An attacker with a GPU cluster can brute-force billions of guesses per second

- Weak passwords fall almost instantly

-

No pepper

- A DB dump gives attackers everything they need to start cracking offline

8. Threat Models and How Hashing, Salting, and Peppering Help

It helps to map mechanisms to threats:

| Threat |

Hashing |

Salting |

Peppering |

| Insider reading passwords |

✅ |

❌ |

✅ (if pepper is hidden) |

| Database breach |

✅ |

✅ |

✅ (if secrets separate) |

| Rainbow table attacks |

✅ (with good hash) |

✅ |

✅ |

| Brute-force with GPUs |

✅ (if slow) |

❌ |

✅ (increases work and requires secret) |

| Credential stuffing reuse |

❌ (that's UX/policy) |

❌ |

❌ |

Hashing is non-negotiable. Salting is mandatory. Peppering is an additional, defense-in-depth measure.

9. Helping Users Choose Strong Passwords

Even the best hashing scheme can’t save a user who picks password123.

You should encourage strong passwords at input time and validate them:

- Minimum length (e.g., 12+ characters)

- Encourage passphrases (e.g., multiple random words)

- Avoid common passwords and known breaches

- Provide immediate feedback on strength

Tools like the htcUtils Password Strength checker can be used during development or testing to evaluate password policies and get a feel for how strong or weak certain passwords are. That can help you tune your minimum requirements and examples in UX copy.

When generating system-level or temporary passwords, use a proper password generator. For manual testing or sample credentials, a tool like the htcUtils Password Generator is handy for quickly producing random, high-entropy passwords that satisfy your policy.

You’ll likely need to support evolving algorithms over time (e.g., migrating from bcrypt to Argon2).

Store enough information to:

- Know which algorithm was used

- Reproduce the hash

- Migrate later

A common pattern:

{

"user_id": 123,

"password_hash": "$argon2id$v=19$m=65536,t=3,p=4$...",

"algorithm": "argon2id",

"created_at": "2025-01-01T12:34:56Z"

}

Many libraries (e.g., bcrypt, Argon2) embed parameters inside the hash string, so you might not need separate fields for salt and parameters.

10.2 Incremental Migration

When you decide to upgrade your algorithm:

- Detect old hashes on login (e.g., by prefix or

algorithm field).

- If the password is correct:

- Rehash using the new algorithm

- Store the new hash

- Over time, active users get migrated; inactive users can be forced to reset on next login.

11. Common Pitfalls (and How to Avoid Them)

11.1 Using Encryption Instead of Hashing

Storing encrypted passwords (with a key you can decrypt) means:

- Anyone with the key (or access to the system) can read all passwords

- It defeats the purpose of “I can’t see your password”

Use one-way hashing, not reversible encryption.

11.2 Reusing the Same Salt

The salt must be:

- Random

- Unique per password

Reusing a salt across users reintroduces the “same password → same hash” issue. Let the library generate salts for you where possible.

11.3 Storing Pepper in the Database

If the pepper is in the database:

- A DB compromise gives the attacker both hash and pepper

- You lose the added benefit of peppering

Keep pepper in environment variables, secret stores, or HSM.

11.4 Not Using Constant-Time Comparison

Comparing hashes with regular == can leak timing information.

Prefer library helpers where available, or use constant-time comparison:

// Node.js example

const crypto = require('crypto');

function constantTimeEquals(a, b) {

const bufA = Buffer.from(a);

const bufB = Buffer.from(b);

if (bufA.length !== bufB.length) return false;

return crypto.timingSafeEqual(bufA, bufB);

}

Most password hashing libraries incorporate constant-time checks internally; use their verify/compare functions.

11.5 Overly Strict or Overly Weak Policies

- Overly strict (complexity rules like “uppercase + number + symbol + no repeated chars”):

- Users pick predictable patterns (

Password1!)

- They forget passwords more often

- Overly weak (8 characters, no checks):

- Easy to brute-force even with strong hashing

A better approach:

- Favor length over complexity

- Block common passwords and known leaks (e.g., “123456”, “qwerty”)

- Use a strength checker during input to guide users

12. Example System Design Overview

Here’s a conceptual architecture for a secure password handling system.

graph TD

U[User Browser/App] -->|HTTPS| A[Application Server]

subgraph Secrets

S[Secrets Manager / Env Vars]

end

subgraph Data

D[(Database)]

L[(Logging/Monitoring)]

end

A -->|Load pepper| S

A -->|Store hash & metadata| D

A -->|Audit & alerts| L

style S fill:#fdf6e3,stroke:#657b83

style D fill:#f0f8ff,stroke:#4682b4

style L fill:#f0fff0,stroke:#228b22

Key points:

- Passwords only exist in plaintext in memory briefly on the app server

- Hashing happens server-side, never in the client (JavaScript hashing in the browser is not a substitute)

- Pepper is loaded from a separate secrets store, not the DB

13. Checklist: Secure Password Storage Best Practices

Use this as a quick reference when reviewing your implementation:

- [ ] Never store plaintext passwords

- [ ] Use a dedicated password hashing function (Argon2, bcrypt, scrypt, PBKDF2)

- [ ] Use per-password salts (usually handled by the library)

- [ ] Store hashing algorithm and parameters with the hash

- [ ] Consider using a pepper stored outside the database

- [ ] Use constant-time comparison when verifying hashes

- [ ] Implement a migration strategy for future algorithm changes

- [ ] Enforce sensible password policies (length, common password blacklist)

- [ ] Give users feedback on password strength (with a checker during input)

- [ ] Use rate limiting and account lockout or progressive backoff on repeated login failures

Conclusion

Secure password storage is not about one magic function—it’s a combination of hashing, salting, peppering, good algorithms, and sane UX. When you:

- Use a modern password hashing function (Argon2, bcrypt, etc.)

- Ensure every password has a unique salt

- Add a well-protected pepper for defense in depth

- Help users pick strong passwords and validate them sensibly

…a database breach turns from “instant catastrophe” into something attackers have to work very hard for, giving you time to respond and protect your users.

Treat password storage as core infrastructure. Get the fundamentals right once, document your approach, and keep an eye on evolving best practices so you can adjust algorithms and parameters over time.